Important Points from the Commercial Code (Transport and Maritime Commerce) Revisions A look at the transport of goods by land, sea and air

2018.05.18 Shiniya YOSHIDA

On 18 May 2018 the “Commercial Code and Act on International Carriage of Goods by Sea Revision Bill” was enacted with its approval by the Diet’s House of Councillors. Also known as the “Commercial Code (Transport and Maritime Commerce) Revisions”, it is the first major revision of the Commercial Code’s provisions on transport and maritime commercial law in approximately 120 years and modernizes and consolidates the laws on transportation and maritime commerce. Along with these revisions, provisions regarding the international transport of goods by sea have also been established.

The Commercial Code’s revised transportation and maritime commerce provisions are areas of law that rarely receive the spotlight from a legal viewpoint, but they are of vital importance to business activities and our daily lives, so this column will introduce the main revisions and important points from the point of view of logistics.

Outline of transportation contracts

Classification

Transportation contracts are classified into the transportation of goods including raw materials like iron ore and food grains, energy sources like crude oil and LNG, as well as finished products for use and consumption on the one hand, and the transportation of people (passengers) on the other.

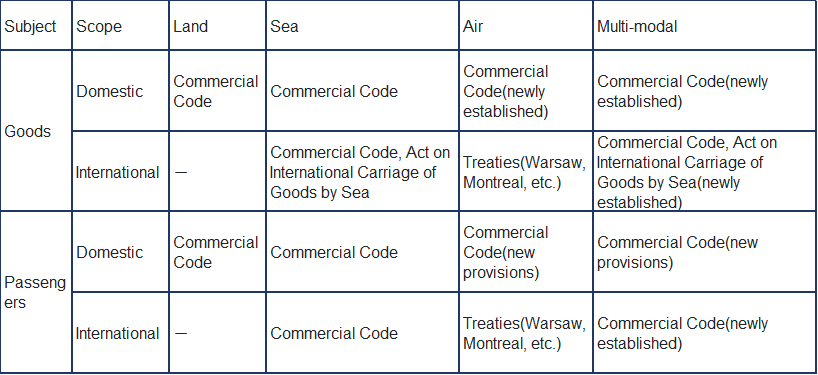

Contracts for the transportation of goods are very important contracts which also affect the management strategies (logistics) of companies. Contracts for the transportation of goods are categorised based on (1) whether they are for domestic or international transport, and (2) whether they are for land (road or rail), sea (ship) or air (aircraft) transport. “Multi-modal” transportation refers to transportation that combines these methods.

Overview of revisions and applicable laws and treaties

The terminology used in the revised Commercial Code has been modernised. On the substantive side also, definition provisions for goods transport and passenger transport contracts and provisions for air and multi-modal transport have been newly established. Also, the inconsistencies that previously existed between the various goods transport regulations have been unified. This relationship can be easily shown in the following table.

Goods Transportation Contracts

The most important revision relating to goods transportation contracts is the enactment of the following “common provisions” that apply to domestic land, sea and air transportation. Along with these, the Act on International Carriage of Goods by Sea has also been revised, so that the same provisions (Articles 1, 2 (1), 3 and 4) also apply to international sea transport.

Shipper’s duties

One important revision is the establishment of a duty for the shipper to declare dangerous goods. If the goods are flammable, explosive or dangerous in any other way, the shipper has a duty to inform the carrier of information important for the safe transport of the goods prior to handing them over, including that the goods are dangerous and the item’s name and chemical properties. Accordingly, if this duty is breached, the shipper will be obliged to compensate the carrier for damages. During the drafting of the revision, there was debate whether the liability should be for negligence or strict liability, but the ministry guideline adopted the former option and the enacted revisions also define it as liability for negligence. This provision also applies to the international transport of goods by sea.

Carrier’s liability for damages

(1) Exclusion of special provisions for high-value goods

An important revision related to carrier’s liability is the establishment of provisions that exclude the application of regulations relating to high-value goods. Under the current Commercial Code, the carrier’s liability is waived if high-value goods are not declared in advance, but the revision prescribes that such waiver will be excluded if loss, damage or delay is caused due to the carrier’s bad faith (when making the contract), intent or gross negligence. This provision also applies to the international transport of goods by sea.

(2) Principles of the Carrier’s Responsibility

The carrier will bear a duty to compensate for and loss or damage (including giving rise to the cause of loss or damage) or delay that occurs between “receipt” and “delivery”. Provisions that fix the quantum of compensation for loss or damage will apply in the case of the carrier’s bad faith or gross negligence, which is the same as under the current Code, but this point differs slightly in the case of international transport of goods by sea. However, the provisions do not apply in the case of mere delay in delivery.

Extinguishment of the Carrier’s Liability

(1) Extinguishment of liability through receipt of the goods

The revised Code provides that the carrier’s liability for damage or partial loss of the goods will be extinguished upon the consignee accepting the goods without objection. However, the consignee has two weeks to notify the carrier in cases where the damage or partial loss cannot be discovered immediately. These limitations do not apply in the case of the carrier’s bad faith, which is the same as under the current Code.

On the other hand, in the case of international transport by sea, the major differences are that the consignee has three days to give notice, and the provisions do not completely extinguish the carrier’s liability.

In the case of international transport by air, the Montreal Convention defines a time limit of 14 days.

(2) The Substance of the Extinguishment of Liability

Under the current Commercial Code, the carrier’s liability for loss, etc. of goods is subject to extinctive prescription after one year. The revised Code changes this to a one-year exclusion period to match international sea transport, which is an important change. Along with this, it will become possible for the parties to agree to an extension of the period, but only when the agreement is made after the loss or damage has occurred.

In the case of international air transport, the Montreal Convention defines a two-year statute of limitations period.

Relationship with Tort Liability

Under a newly added provision, the abovementioned provisions that (1) quantify damages, (2) define special rules for high-value goods, and (3) extinguish the carrier’s liability after certain periods of time will also apply to the carrier’s tort liability for loss, etc. of goods. Further, the limits on the carrier’s liability will also apply to the liability of the carrier’s employees. This point is particularly important in practice and requires caution, especially regarding the extinguishment of the carrier’s liability to compensate for damages. The same provisions also apply to international sea transport of goods.

Other

Advance payments have been removed from the list of claims that may be secured by the carrier exercising their right of retention over goods, while costs incidental to the retention (e.g. storage fees) has been added. The revisions also prescribe that a consignee who is not a party to the transportation contract acquires the same rights as the shipper in the case that the entire shipment is lost, and the shipper cannot exercise those rights if the consignee makes a claim for the delivery of the goods or compensation for damage.

Passenger transport

The current Commercial Code provisions relating to passenger transport by sea have been repealed and replaced with unified provisions that apply to domestic passenger transport by land, sea or air. Where the governing law of a contract is Japanese law, these provisions will also apply to international passenger transport by sea.

Carrier’s Liability

Contract provisions that seek to limit the carrier’s liability for injury to the life or body of a passenger caused by reasons other than delay will be invalid (a newly-established unilateral mandatory provision), which adopts a viewpoint of respecting life and protecting consumers. However, (1) transport during a large-scale disaster and (2) the transport of passengers who face a risk of serious danger to their life or body even during standard transportation are excluded.

Carrier’s Liability for Passengers’ Hand Luggage

The revised Commercial Code provides that the carrier will not be liable for the loss or damage of hand luggage that the passenger does not hand over to the carrier, unless such loss or damage is caused by the carrier’s intent or negligence; it has also been clearly defined that this includes the passenger’s personal effects. A newly-established provision that extends the application of the provisions relating to quantification of damages, extinguishment of the carrier’s liability and the relationship with tort liability (other than the provisions relating to high-value goods) to hand luggage also is a distinctive feature.

Maritime Commercial Law

The parts of the Commercial Code relating to maritime commerce are probably unfamiliar to people other than those in the industry. However, it is said that sea transportation accounts for 40% of domestic transport (by ton-kilometre) and 99% of international transport (by weight), so the revisions to the Code’s provisions on maritime commerce are very important.

Contracts for Sea Transportation of Goods

Contracts for the transportation of goods by sea can be categorised into carriage contracts which governs the transport of individual goods, and charter contracts in which the vessel used to carry goods is the subject of the contract. For the former, bills of lading are generally used in international transactions. Regarding the latter, in practice they can be further divided into bare-boat charters, time charters and voyage charters (strictly speaking, the revised Commercial Code defines bare-boat charters and time charters as contracts relating to the use of the vessel).

A bare-boat charter contract is the lease of the vessel, but a distinctive feature of the revisions is the addition of a provision making the charterer responsible for the repair of the vessel. Time charter contracts are an important contract that have long been frequently used both in domestic and international trade, so the new provisions inserted in the revised Code are worth special mention. Voyage charter contracts are transportation contracts which were covered in the current Commercial Code and have been revised to conform with current business practices.

Special Provisions relating to Transportation of Goods by Sea

(1) Voyage charters, cargo transport

Revisions regarding the obligation to ensure the seaworthiness of the vessel and the prohibition of contract provisions that waive liability are particularly important. Under the current Commercial Code, the obligation to ensure seaworthiness is one of strict liability, but it has been revised to liability for negligence, to match international sea transport, which is an important change. The same obligation which applies to voyage charters is a default provision that can be waived, but it is a mandatory provision between the carrier and the bill of lading holder, so the obligation is a mandatory provision for the carriage of individual freight.

(2) Bills of Lading, Sea Waybills

The provisions governing bills of lading differ for domestic and international sea transport, but currently bills of lading are rarely used in domestic trade. The revisions to the Commercial Code make the domestic provisions the same as for international sea transport, and the difference between loading bills and receipt bills have been made clear. Provisions regarding sea waybills (non-negotiable instruments) that are used in practice to address the “bill of lading risk” have been newly added and other provisions have been modernised to allow for the supply of bills by electronic means.

Vessel Collision

(1) Apportionment of Liability Between Shipowners

A revision has been made to the provisions that apply when a vessel collision occurs. If there is negligence by any vessel’s owner or crew, the courts will be required to consider the severity of this negligence when apportioning liability and quantifying the damages, and if the level of negligence is unclear, then liability and the quantity of damages will be apportioned evenly between the owner of each vessel.

(2) Extinctive Prescription and Scope of Applicability

Claims arising from a vessel collision are subject to a one-year extinctive prescription period, which differs from the two-year period defined under international conventions. Previous court precedents have ruled that the period commences when the party which suffered damage becomes aware of the damage and the party that caused it. However, the revision to the Code defines that where the cause of the collision (including circumstances analogous to a collision) is a tortious act (limited to damage to property rights), the two-year extinctive prescription period will commence from the time of the tortious act. Note that the Civil Code applies in the case of personal injury.

General Average, Salvage

Because general average is often handled in accordance with the 1994 York-Antwerp Rules in practice, the revisions to the Commercial Code regarding declaring general average and determining contributions have been made consistent with the Rules.

The Commercial Code’s provisions relating to salvage have been revised to define a two-year extinctive prescription period (calculated from the date the salvage operation ends) to correspond to the 1910 convention on salvage (which Japan has ratified) and the 1989 International Convention on Salvage (which Japan has not ratified) that contracts used in practice adopt from an environmental protection standpoint.

Marine Insurance

Because international standards relating to marine insurance have been developed over a long period based on the accumulation of court precedents centred on English law and practical experience, the existing Commercial Code provisions have been retained, but the duty to notify has been changed to a duty to voluntarily declare and provisions relating to abandonment, etc. have been deleted in order to correspond with industry practice.

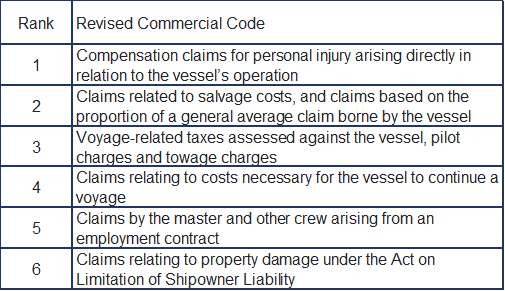

Maritime Liens

Changes to the priority ranking of lien claims are an important revision. There was a proposal to give partial priority to ship mortgages during the revision’s deliberation process, but this was not included in the final revision. Also, the scope and ranking of lien claims was changed, with unpaid freight costs removed and personal injury added.

Concluding thoughts

The revisions that have been made to the Commercial Code are generally based on commercial practice, so in that sense they have been viewed as not having a large effect on current practices. However, from the point of view of a lawyer involved in all matters relating to transport, ports and warehousing businesses, the way that the revisions have to some extent resolved some important issues can be highly regarded as making a substantial contribution to the prevention of unnecessary disputes.

The standard contract terms and conditions published by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport are extremely important because they are adopted as the contents of standard contracts used in the transport and warehousing industry. Therefore, the Ministry is likely to publish revised terms based on the revisions to the Commercial Code that have been discussed above.